Measuring Resting Heart Rate

From manual pulse counts to the latest in app technology, dive into the transformative journey of heart rate monitoring

Home » Stress & Energy » Not just fight or flight: how stress affects your body and brain

You’re walking home late at night when you suddenly spot a silhouette up ahead. Immediately, you experience an emotional response: fear. But a split second before you become conscious of your fear, your body has already launched the chemical reaction we call “stress.”

It all starts in the amygdala, the two-part region in the temporal lobes of your brain, which monitors all external stimuli, trying to identify any information that could be dangerous to your life or health.

The amygdala instantly juxtaposes signals from the sensory organs (the silhouette in the dark) with memories of similar situations in the past ( a friend of yours was mugged walking late at night) and general knowledge (this neighborhood isn’t safe after dark), concluding that you’re in danger. The alarm signals are then sent to the diencephalon, from which the hypothalamus launches the ancient “fight or flight” response.

This releases hormones into your body to put it into battle readiness. Adrenaline speeds up your pulse and breathing, and blood starts pumping to your tensed muscles. To maximize your energy reserves for this incoming threat, cortisol signals glucose to be released into the bloodstream, while your immune response, anti-inflammatory processes, and digestion are all slowed down.

Stress fills us with strength and endurance to give us a better shot at surviving a dangerous situation. But this is a very energy-consuming process, and your body isn’t designed to be able to handle it for prolonged periods. In a perfect world, your body would return to its initial relaxed state as soon as you realize that the silhouette was just a cat crossing the street. But in the real world, stress can linger for a long time, rising and falling but never fully subsiding since we’re constantly surrounded by stressors. Between work, family arguments, financial difficulties, or existential fears, these stressors aren’t as easy to dismiss as a momentary scare in a dark alley.

On the physiological level, chronic and acute stress responses look the same. We generally don’t notice this because the chronic stress response is not as intense: your breathing is shallow but not as elevated; your muscles are tensed, but not as much, like a tighter jaw and raised tight shoulders. Still, chronic stress uses up an enormous amount of resources, and important organ systems suffer as a result.

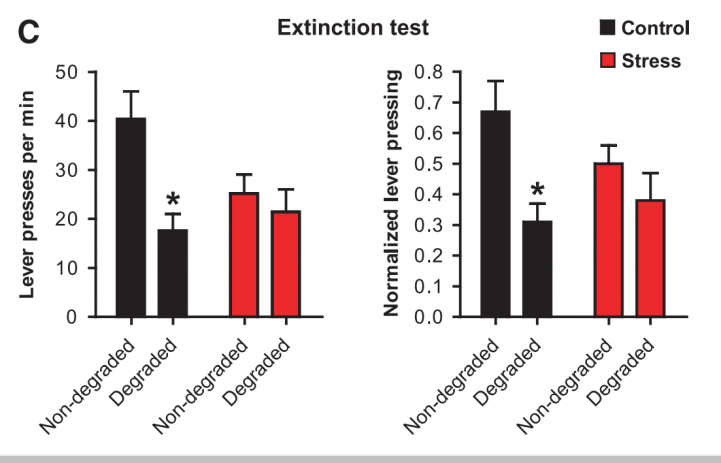

Chronic stress rearranges your brain’s neural pathways. This harms your ability to orient yourself in space, as well as your working memory and ability to learn. It even changes your decision-making mechanisms. In one experiment, mice were taught to press two levers to receive treats from two feeders. The mice were then separated into two groups, with one group being subjected to chronic stress conditions for three weeks. After that, the lever rules were changed: one feeder no longer required a lever press to dispense a treat. However, the mice from the stress group continued to press both levers. Brain scans showed that they had reduced activity in their prefrontal cortex, the area responsible for analyzing situations and decision-making. Their sensory-motor region, on the other hand, was hyperactive. It is likely that stress made these mice default to a known strategy, despite the reality of their new circumstances and the altered results of their behavior.

A team of psychologists and neurobiologists from Great Britain, Germany, and the USA reached this conclusion after they conducted an experiment in which 91 people played an economics game.

The participants had to look at images of smartphones and TVs as they glided in front of them on a virtual assembly line and determine what kind of factory the assembly line was located in: a TV factory or a smartphone factory. Then every participant would “invest money” into producing either TVs or smartphones. The subject received a monetary reward if they identified the factory correctly (and it matched the product they invested in) and lost money if they were incorrect. Before the experiment, half of the participants were told that they would need to give a speech in front of a commission, increasing their stress levels.

The result? The more stressed a participant was, the more likely they were to incorrectly identify the factory that would have led to a reward. The study authors note that for the subjects in a stressful situation, every counterargument against their guess weighed more on them than if they were relaxed. From a physiological perspective, this makes sense: pessimism is more likely to prepare you for the worst possible outcomes. But if your goal is to make a maximally objective decision about your future, it is best to avoid the influence of any stressors.

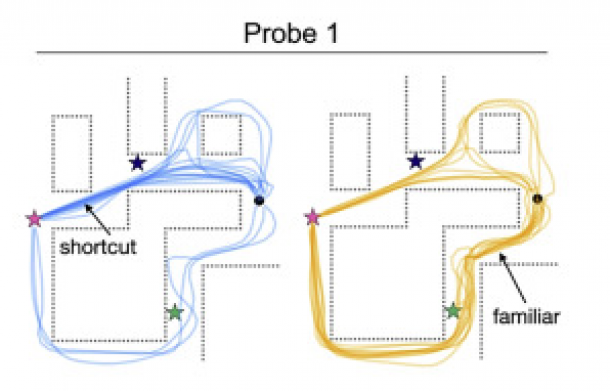

Researchers at Stanford University conducted an interesting study in which 38 participants used VR goggles to study a fixed route through the streets of 10 different cities. They were then “transported” to one of the virtual cities and asked to navigate to a particular spot on the map. Half of the participants were told that they would occasionally experience an electric shock, creating a stress reaction. The researchers then analyzed how the stressed and non-stressed participants planned their routes. The results showed that the participants who weren’t threatened with an electric shock were much more likely to find a shorter and easier route. The participants in the stressed group were more likely to use the fixed route that they had already learned previously, ignoring any potential shortcuts or ways to improve their route.

An MRI analysis showed that stress inhibits activity in the hippocampus, the brain region responsible for memory. This is why the stressed participants didn’t have the capacity to improvise their route, instead acting on autopilot. The connection to future planning comes from the fact that, in order to plan for the future, you need to use a particular kind of memory. Future planning is a form of “remembering” the future, the capacity to keep in mind the things you need to do at a later time. According to the study’s authors, stress inhibits this function as well.

Welltory Team, 29 Sept. 2022

From manual pulse counts to the latest in app technology, dive into the transformative journey of heart rate monitoring

Discover the intricate relationship between late-night eating and its impact on sleep duration and quality

From boosting cognitive function to enhancing physical performance, discover the impact of blood oxygen levels on various aspects of health

The relationship between stress and productivity and how Welltory can help you plan better

Does sleeping burn any calories, should you exercise right before bed and how much do you need to sleep to burn a 1000 Cal

All you needed to know about headaches at night – types of nighttime headaches, their causes, possible treatment and how to avoid them.

App Store

App Store

Google Play

Google Play

Huawei AppGallery

Huawei AppGallery

Galaxy Store

Galaxy Store